Can scientists predict the climate if they struggle to forecast the weather? It’s a question that resurfaces often, for example, a few years ago, in a Guardian article quoting UK Business and Energy Minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, who dismissed climate projections as unrealistic because “meteorologists struggle to correctly predict the weather.”

While this statement may sound logical at first glance to some, it’s based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between weather and climate: a distinction that’s crucial to understanding climate science, risk, and resilience.

So, what is the difference between weather and climate? And how can scientists make reliable projections about our climate future?

Let’s break it down.

Weather vs climate: Definitions and key differences

Weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions in a specific place and time, like a rainy Wednesday in San Francisco or a heatwave in Madrid. It’s what you experience day to day, and it’s influenced by variables such as:

- Temperature

- Wind speed

- Barometric pressure

- Precipitation (rain, snow, hail)

Weather forecasts use computer models to simulate these conditions based on current observations, known as initial conditions.

These models can predict changes over hours or days, but their accuracy decreases the further out they go. That’s because the atmosphere is chaotic and sensitive to small changes, making long-term weather prediction inherently difficult.

Climate, on the other hand, describes the average weather patterns over a much longer period, typically 30 years or more, as recommended by the World Meteorological Organization. It’s not about predicting the weather on a specific day, but understanding broader trends and the likelihood of events like droughts, floods, or heatwaves.

In short:

- Weather is what you get.

- Climate is what you expect.

A relatable analogy: Boiling water

To understand the difference between weather vs climate, imagine a pan of boiling water:

- A weather forecast would try to predict the exact location of each bubble rising to the surface.

- A climate projection would estimate how the overall temperature of the pan changes over time, based on the heat source.

Weather is about the details; climate is about the pattern. And climate change? That’s like turning up the heat on the stove.

Weather vs climate misconceptions in media and politics

Public discourse around climate change often suffers from a lack of clarity, especially when weather and climate are used interchangeably. This confusion is sometimes amplified by political statements or media coverage that misrepresent scientific concepts.

Take, for example, the claim that climate projections are unreliable because weather forecasts are imperfect. While it’s true that weather forecasts become less accurate over time, this has little bearing on the reliability of climate projections, which are based on long-term statistical patterns and physical laws governing the Earth system.

Misunderstanding the difference between weather vs climate can lead to misguided policies, delayed action, and public scepticism. That’s why scientific literacy — and clear communication is essential. At Mitiga Soutions, we believe that empowering decision-makers with accurate, accessible climate intelligence is key to building a more resilient future.

Why climate can be predicted, even if weather can’t

While weather changes rapidly, climate evolves slowly. That’s because the climate system includes components like the ocean, which has a much longer memory than the atmosphere.

Ocean currents, sea surface temperatures, and other slow-moving processes provide a stable foundation for long-term projections. Climate scientists use climate models, not weather forecasts, to simulate how the Earth’s climate responds to different conditions, such as rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

These models incorporate:

- Atmospheric physics

- Ocean dynamics

- Land surface processes

- Biological and chemical interactions

The latest generation of Earth System Models goes even further, simulating how vegetation, soil, and ocean life (like phytoplankton) interact with the climate. For example, they can show how warming temperatures affect carbon sinks and sources, helping us understand how the biosphere influences atmospheric CO₂ levels.

These models don’t aim to predict the weather on a Tuesday in 2050. Instead, they help us understand how climate change will shape the frequency and intensity of weather events, from heatwaves to hurricanes, over decades.

{{quote-1}}

Why we need climate projections

The Earth’s climate is a chaotic system, meaning it’s highly sensitive to initial conditions. Small changes can lead to large, unpredictable outcomes. But that doesn’t mean climate projections are impossible.

By combining historical climate data with advanced modelling, scientists can estimate the likelihood of future events. For example, while we can’t predict the exact day a heatwave will hit the UK, we can project that such events will become more frequent and intense over the next 20 years.

Real-world example: City water management

Imagine you’re a city water manager. You need to know:

- Will there be enough rain to replenish aquifers and supply drinking water?

- How likely is it that heavy rainfall could overwhelm drainage systems and cause flooding?

Weather forecasts help you plan for the next few days. But climate projections are essential for long-term infrastructure planning, from flood defences to drought mitigation systems.

Seasonal climate predictions, based on patterns like El Niño, help estimate climate conditions over months. Climate projections go further, modelling how long-term changes in CO₂ levels will affect rainfall patterns over decades.

How climate intelligence helps us adapt and build resilience

Understanding climate isn’t just about science, it’s about survival, strategy, and smart planning.

Climate projections are critical tools for governments, businesses, and communities preparing for a future shaped by climate change.

They inform:

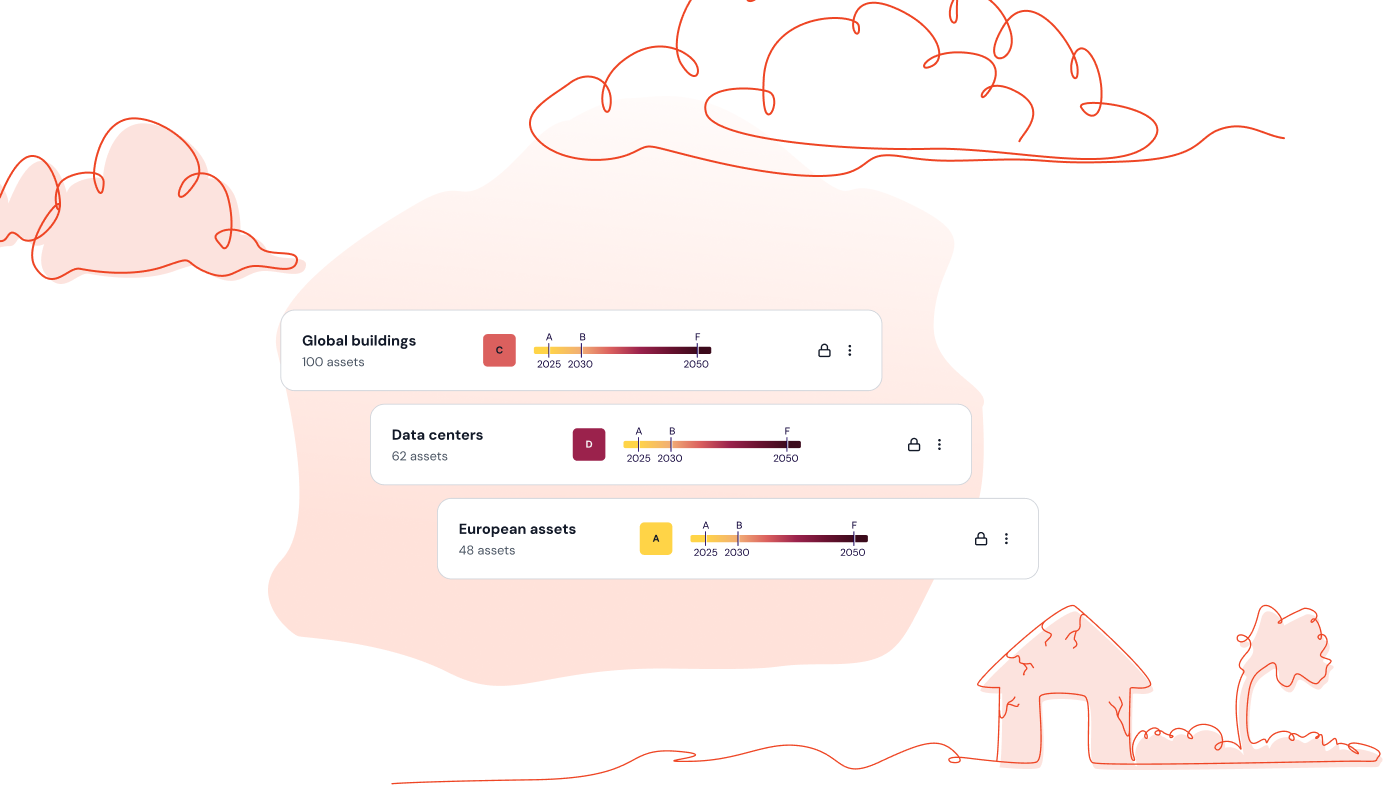

- Infrastructure design: Engineers use climate data to build bridges, roads, and buildings that can withstand future heatwaves, floods, or sea-level rise.

- Insurance and finance: Risk modellers rely on climate intelligence to assess exposure to physical climate risk and price policies accordingly.

- Agriculture and food security: Farmers and policymakers use seasonal forecasts and long-term projections to plan crop cycles and manage water resources.

- Disaster preparedness: Emergency planners use climate scenarios to anticipate extreme events and develop response strategies.

At Mitiga Solutions, we specialise in translating complex climate science into actionable insights. Our modelling capabilities help stakeholders understand not just what might happen, but how to prepare, adapt, and thrive in a changing climate.

How climate change affects the weather

Here’s another analogy, this time from sport. Imagine putting a golf ball towards a hole. The hole represents an extreme weather event. The climate determines how far you stand from the hole.

With a warming climate, we’re standing closer to the hole, making it easier to “score” an extreme event. That’s why heatwaves, floods, and storms are becoming more frequent and intense.

Take Hurricane Harvey (2017). It picked up vast amounts of moisture from the Atlantic and dumped it on Texas. Why? Because warmer air holds more moisture, a relationship described by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Climate change didn’t cause the hurricane, but it amplified its impact.

The past gives us confidence in the future

Climate scientists have studied geological records stretching back millions of years. These show a clear link: when CO₂ levels rise, so do global temperatures, sea levels, and ice melt.

Today’s CO₂ levels (~417 ppm - 427ppm) match those from three million years ago. If emissions continue unchecked, we could reach levels last seen 14 million years ago, when Greenland had no permanent ice sheet.

Recent studies show that 27 cm of sea-level rise from Greenland’s melting ice is already locked in. That’s a serious risk for low-lying coastlines worldwide.

Climate projections are possible and necessary

Climate models are rigorously tested against past events. These tests show that models are generally highly skillful at reproducing current climate and past climate changes.

While projecting the climate is challenging, it’s far from impossible. In fact, it’s essential.

Understanding the difference between weather vs climate helps us prepare for the future. Weather is short-term and local. Climate is long-term and global. They’re different, but deeply connected. More like first cousins than twin siblings.

To explore more key concepts like these, visit Mitiga Solutions’ climate intelligence glossary and deepen your understanding of the science behind climate risk.