2026 is shaping up to be a year where physical climate risk becomes both more visible and more financially material. Across insurers, asset managers, corporates, regulators, and technology providers, climate risk is moving out of reports and into the mechanics of real decisions.

The 12 predictions below focus not on climate science itself, but on how organisations are beginning to act on physical climate risk as pressures intensify and expectations evolve. They reflect observable shifts in how risk is priced, allocated, governed, and operationalised across markets and sectors.

How these predictions were developed

These predictions are based on observed shifts across financial markets, insurance, regulation, infrastructure, and corporate decision-making. They reflect changes already visible in procurement policies, credit processes, investment governance, and contract structures, rather than long-term climate scenarios or theoretical modelling.

1. Physical climate risk moves from ESG reports into procurement and credit decisions

For most organisations, physical climate risk has lived at the edges of decision-making. It appears in sustainability reports, risk registers, and regulatory disclosures, but rarely shapes who companies buy from, lend to, or finance.

That begins to change in 2026. As climate-related disruptions become more frequent and more costly, companies expand their risk lens beyond owned assets to the full value chain. Heat-related shutdowns, port closures, water shortages, wildfire disruptions, and grid failures expose a hard truth: supplier resilience directly affects operational continuity.

Procurement teams start integrating site-level climate exposure into supplier selection, contract renewal, and diversification strategies. Location, hazard exposure, and adaptive capacity begin to matter alongside price, quality, and lead times. In critical sectors, reliance on single suppliers in high-risk regions increasingly triggers contingency planning or replacement.

The same logic extends into financial decision-making. Banks and lenders embed physical climate risk into credit assessments, supply-chain finance programmes, and covenant structures. Assets and counterparties exposed to foreseeable hazards face higher risk premiums, tighter terms, or additional conditions. In some cases, resilience investment becomes a prerequisite for favourable financing rather than a voluntary sustainability add-on.

By 2026, physical climate risk is no longer treated as narrative context. It becomes:

- A procurement scoring variable alongside cost and reliability

- An input into credit pricing, covenants, and counterparty limits

- A contractual consideration shaping liability and performance expectations

The shift is subtle but structural. Climate risk moves from something organisations explain after the fact to something they price, select, and contract against in advance.

Prediction trigger: More than fifty S&P 500 firms formally integrate physical climate risk into procurement scoring frameworks; global banks publish lending or supply-chain finance policies that explicitly reference asset-level physical risk.

2. One-size-fits-all climate models lose decision relevance, and customisation becomes the standard

As physical climate risk enters procurement, credit, and investment decisions, a new tension emerges: many of the models organisations rely on are no longer fit for the decisions being made.

For years, generic hazard layers, predefined asset categories, and high-level risk scores were sufficient for disclosure and portfolio screening. They helped answer questions like “Are we exposed?” or “Which regions are higher risk?” But they struggle when the question becomes “What should we do differently?”

Over the next 12-24 months, that gap becomes increasingly difficult to ignore. Generic models are no longer robust enough for decisions involving underwriting, credit spreads, capital allocation, or M&A valuation.

Decision-makers need insights that reflect how assets actually behave under stress. Two facilities exposed to the same flood depth may experience very different impacts depending on elevation, materials, equipment placement, redundancy systems, or recovery capacity. Likewise, two suppliers in the same region may face very different disruption risks depending on logistics dependencies, workforce exposure, or adaptation measures already in place.

Generic models flatten these differences. As a result, they are harder to defend in credit committees, investment memos, underwriting decisions, or board discussions.

In response, expectations shift. Organisations increasingly demand climate-risk analysis that can be adjusted to reflect:

- Asset-specific characteristics rather than broad categories

- Local conditions and micro-hazards, not just regional averages

- Operational resilience measures and adaptation investments

- Financial thresholds aligned to real decision criteria

The question is no longer whether climate risk is material, but whether the models used to quantify it are defensible enough to support real financial and operational decisions.

Prediction trigger: Climate-risk providers expand configurable modelling approaches; large organisations formally adopt bespoke physical-risk assumptions for credit, investment, or procurement decisions.

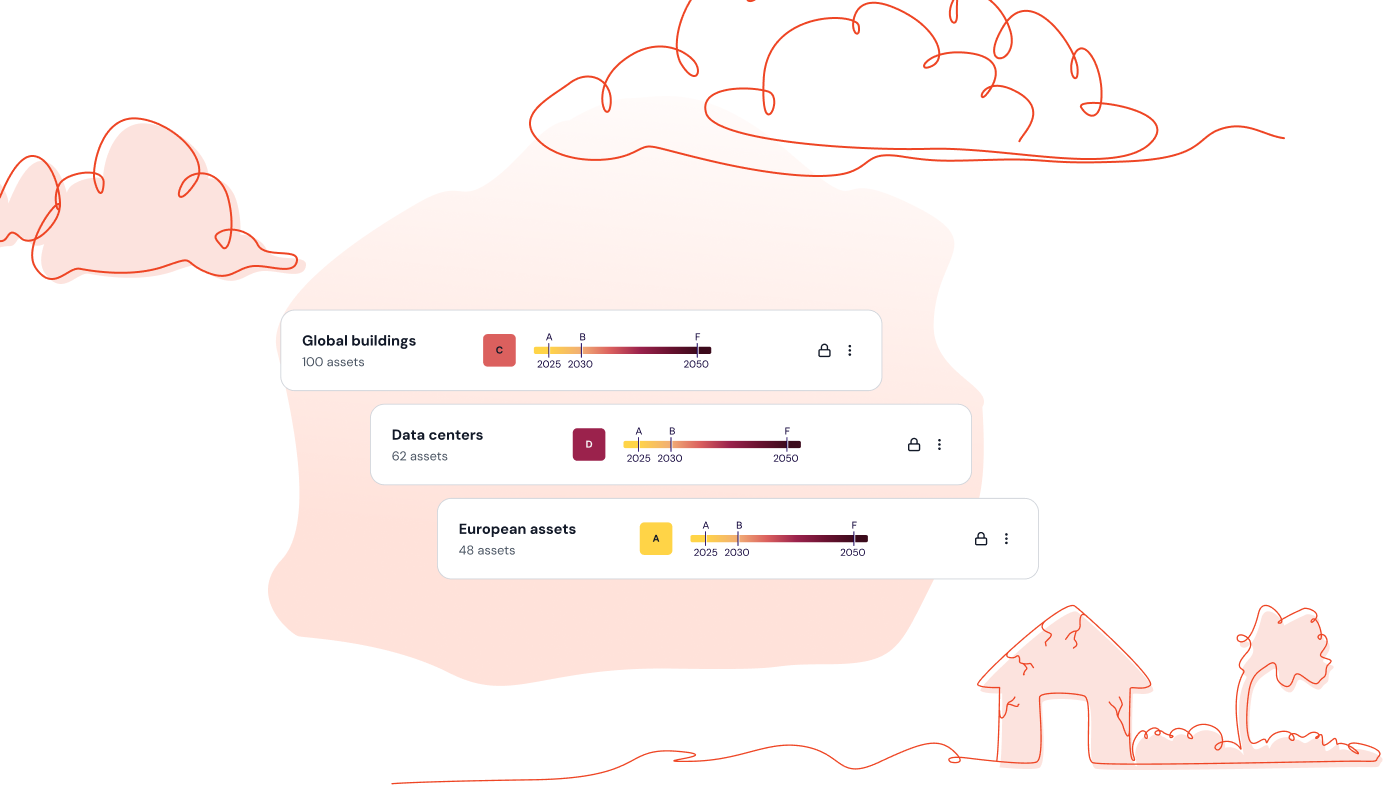

3. Portfolio climate triage goes mainstream for real-asset investors

As modelling becomes more decision-relevant, investors face a practical reality: not all assets can be treated the same way.

Rising adaptation costs, declining insurability, and increasing operational disruption push real-asset investors to move from passive risk awareness to active portfolio triage. Climate risk is no longer something to “monitor everywhere”; it becomes something to manage differently across assets.

Investors increasingly classify assets into a small number of strategic categories:

- Hold and adapt: assets where resilience investments protect long-term value

- Hold and monitor: assets with manageable medium-term risk but limited near-term intervention

- Exit later: assets where long-term risk undermines future value but near-term cash flows remain attractive

- Exit now: assets where climate risk materially threatens operability, insurability, or resale value

This approach reflects capital discipline rather than climate ideology. When insurance availability declines, downtime becomes more frequent, or adaptation costs erode returns, climate risk becomes a portfolio optimisation problem.

Climate triage is no longer an ad hoc exercise. It becomes embedded in investment governance for infrastructure, real estate, energy, and other asset-heavy portfolios.

Prediction trigger: Asset managers publish formal climate-triage frameworks and disclose how physical climate risk informs adapt-versus-exit decisions at portfolio level.

4. Hazard-adjusted EBITDA becomes standard in M&A and investment decisions

As portfolio-level triage takes hold, its implications increasingly surface where value is negotiated: mergers, acquisitions, and capital deployment.

Historically, physical climate risk sat outside core valuation models. It might appear as a qualitative risk factor or diligence appendix, but rarely altered EBITDA assumptions, discount rates, or deal structure in a meaningful way. By 2026, that separation erodes.

Investment teams begin adjusting cash-flow projections to reflect climate-driven operational impacts. These include expected downtime from extreme events, higher operating costs due to heat or water stress, rising insurance deductibles, and capital expenditure required to maintain operability under future conditions. In asset-heavy sectors, these adjustments are no longer viewed as speculative. They are treated as foreseeable and therefore priced in or penalised.

As a result, EBITDA becomes increasingly hazard-aware. Sellers with credible adaptation strategies are better positioned to defend forward projections, while buyers apply pressure where climate risks appear underpriced or unmanaged.

Climate risk also moves earlier in the deal process. It informs investment committee discussions before exclusivity, rather than emerging late as a negotiation friction. Over time, this raises the bar on data quality and assumption transparency.

Hazard-adjusted EBITDA is no longer an exception. It becomes a standard lens through which physical assets are priced, financed, and compared.

Prediction trigger: Public transactions or investment disclosures explicitly reference physical climate risk assumptions influencing valuation, pricing adjustments, or deal structure.

5. Grid and water constraints become enterprise concentration risks

Over the next 12 months, climate-driven stress on electricity and water systems emerges not just as an engineering concern, but as a strategic business risk. Heat waves, prolonged droughts, and rising demand create operating environments where energy and water availability shape where and how businesses can expand.

Electricity grids are built around historical climate patterns. As temperatures rise, extreme heat increases peak demand while reducing infrastructure efficiency and reliability. Water scarcity further complicates energy supply, as hydropower and thermal generation depend on consistent water availability for cooling and operation. Together, these pressures increase the likelihood of shortages, curtailments, and price volatility.

For businesses with significant real-asset footprints, location strategy becomes inseparable from resource resilience. Decisions about expansion, diversification, and long-term site commitments increasingly hinge on the reliability of local electricity grids and water systems. In sectors such as semiconductors, chemicals, food processing, and data centres, failing to account for these constraints materially increases operational risk.

Prediction trigger: Major industrial, manufacturing, or data-centre projects are delayed, relocated, or redesigned due to documented electricity or water-availability constraints linked to climate conditions.

6. Climate-aware digital twins move from demos to operations

What began as proof-of-concept demonstrations increasingly anchors itself in operational decision-making by 2026. Early digital twins focused on equipment monitoring and predictive maintenance. As climate risk intensifies, organisations begin integrating dynamic climate and hazard data into these systems.

A climate-aware digital twin blends:

- Live operational data from sensors and enterprise systems

- Climate hazard projections such as heat, flood, drought, or wind stress

- Scenario analytics aligned with future operating conditions

Together, these elements enable decision support for maintenance scheduling, routing optimisation, inventory buffering, cooling and energy management, and emergency planning. The shift is from static asset representation to climate-integrated operational logic.

As adoption matures, digital twins move beyond engineering teams. Operational leaders and risk managers use them to identify failure points that historical-only models miss and to prioritise adaptation investments over time.

Climate-aware digital twins are no longer experimental. They become embedded tools for managing operational resilience.

Prediction trigger: Three major digital-twin platforms or vendors launch climate-module extensions that are adopted in 500+ enterprise deployments across sectors such as infrastructure, energy systems, logistics, or urban operations, signalling that climate-aware twins have crossed from niche use cases into broader operational practice.

7. Insurance retreat accelerates and parametric coverage becomes the SME default

For more than a decade, insurers have warned that physical climate risk is outpacing traditional underwriting assumptions. This year, those warnings increasingly translate into market outcomes.

Across regions and hazards, insurers respond to rising losses by tightening terms. Premiums rise, coverage limits shrink, deductibles increase, and hazard-based exclusions become more common. In some locations, coverage is withdrawn entirely. While large corporates may still negotiate bespoke solutions, SMEs feel the impact most acutely.

As a result, a protection gap once discussed mainly at policy level becomes a day-to-day operational issue.

Against this backdrop, parametric insurance moves from niche product to practical default. Rather than indemnifying losses after lengthy claims processes, parametric policies pay out automatically when predefined thresholds are met. The focus shifts from loss replacement to speed and liquidity.

For SMEs, fast access to cash after an event can be the difference between continuity and prolonged shutdown. For insurers and reinsurers, parametric structures offer clearer exposure limits and more predictable risk.

In 2026, parametric coverage is no longer treated as experimental. It becomes embedded into banking products, trade finance, and digital platforms used by SMEs to manage risk.

Prediction trigger: Major insurers and reinsurers formally tighten underwriting criteria or withdraw capacity in climate-exposed regions, as documented in industry loss reports; at the same time, global development banks and reinsurance groups report rapid growth in parametric insurance adoption, with hundreds of thousands of active policies worldwide, particularly among SMEs and emerging-market enterprises (e.g. Swiss Re sigma reports; World Bank and OECD work on parametric risk transfer).

8. Contracts adopt climate-attribution and force-majeure updates

As physical climate risk becomes increasingly foreseeable, contractual language evolves.

Extreme weather events were long treated as exceptional and unpredictable, comfortably covered under force-majeure clauses. By 2026, that assumption weakens. When hazards are known to be increasing and credible risk information exists, blanket claims of unpredictability become harder to defend.

Legal teams respond by revisiting how climate risk is allocated across contracts. Supply agreements, concessions, project finance documents, and long-term service contracts increasingly include explicit treatment of physical climate risk.

Rather than relying on generic clauses, contracts begin defining climate-attribution thresholds, adaptation obligations, operational performance expectations under stress, and disclosure requirements related to risk and mitigation.

This reflects a broader legal shift. Climate risk is no longer viewed solely as an external shock, but as an operational factor that can and should be managed.

Prediction trigger: More than ten publicly disclosed contracts explicitly reference physical climate risk, adaptation obligations, or climate-attribution logic; at the same time, multiple court cases or arbitration proceedings centre on disputes over whether climate-related disruption was foreseeable and adequately managed.

9. Public climate-loss registries emerge to close the protection gap

As economic losses from extreme weather rise, a persistent problem becomes harder to ignore: loss data remains fragmented and inconsistent.

Information is scattered across insurers, governments, emergency agencies, and private actors, often reported using incompatible definitions. This limits the ability to assess which hazards drive losses, where uninsured impacts concentrate, and which adaptation measures reduce damage.

Governments begin addressing this through systematic public reporting. Climate-loss registries emerge as event-level databases documenting physical impacts, economic losses, and insured versus uninsured components.

Designed for forward-looking risk management, these registries link losses to hazard characteristics, asset types, and exposure patterns. They provide a shared reference point for pricing, planning, and adaptation coordination.

By making uninsured losses visible, registries also sharpen focus on the protection gap.

Prediction trigger: A G20 economy formally launches a national climate-loss registry or mandates open, standardised reporting of event-level climate damages and uninsured losses.

10. Cities attach “just resilience” requirements to permits

As climate impacts intensify at neighbourhood level, cities face a dilemma: adaptation investment is urgent, but unmanaged market responses risk accelerating displacement.

Over the next months, more cities embed resilience obligations into planning and permitting rules. Rather than treating resilience as an optional feature, they require developers to contribute to flood protection, heat mitigation, or community resilience funds in climate-exposed areas.

The goal is not to block development, but to prevent new projects from externalising climate risk onto surrounding communities.

By 2026, climate resilience considerations increasingly shape everyday permitting decisions, influencing project costs, design, and timelines.

Prediction trigger: Multiple large cities introduce or formalise planning rules that require resilience contributions or adaptation investments as a condition for permitting new developments in climate-exposed areas.

11. EU regulatory “simplification” backfires, and predictability becomes the new premium

European climate regulation is ambitious. But in the next years, regulatory volatility begins to undermine investment confidence.

Frequent updates to CSRD, ESRS, taxonomy guidance, and due-diligence rules create uncertainty for organisations planning long-term adaptation investments. While direction is clear, shifting details make it harder to commit capital.

As a result, some companies delay or re-sequence climate-related investments, waiting for greater regulatory clarity. This reflects uncertainty, not resistance.

Predictability becomes a competitive advantage. Companies increasingly favour jurisdictions with stable frameworks and credible timelines when planning resilience capex.

Prediction trigger: Industry bodies and business associations publicly cite regulatory volatility as a barrier to climate-related investment planning; multinational companies reference uncertainty around evolving EU requirements when deferring or reallocating adaptation and resilience capital.

12. Adaptation finally takes centre stage as companies tire of mitigation theatre

After years of increasingly sophisticated disclosure, organisations confront a gap between reporting quality and real-world outcomes.

By 2026, priorities rebalance. Adaptation moves from the margins to the core of operational and financial planning. The focus shifts from long-term targets alone to near-term operability and resilience.

CFOs and investment committees increasingly direct capital toward cooling, water security, backup energy, flood protection, and supply-chain hardening. These investments are no longer framed as optional safeguards, but as prerequisites for performance.

Adaptation capacity becomes a signal to investors, lenders, and insurers of long-term viability.

What we’ll see:

- Adaptation and resilience budgets grow >25% YoY among large corporates

- Sustainability benchmarks and ratings introducing explicit measures of resilience and adaptation performance

- Adaptation capacity emerging as a differentiator in capital allocation, insurance availability, and competitive positioning

Prediction trigger: Large listed companies explicitly disclose separate adaptation or resilience capex lines in financial or sustainability reporting; major investors, credit-rating agencies, or ESG benchmark providers introduce scoring methodologies that assess physical resilience and adaptation performance alongside emissions metrics.

Conclusion

2026 marks the point at which physical climate risk becomes embedded in real decisions across procurement, lending, investment, insurance, operations, and capital allocation.

Organisations that perform best in this environment will be those that move from reporting to resilience, from generic assumptions to tailored insights, and from stated intent to operational execution.

Climate resilience is no longer a peripheral cost. It is a performance advantage, a valuation driver, and a competitive differentiator.

Disclaimer: This article does not attempt to predict climate change itself. Instead, it takes a focused stance on the trends reshaping the climate-risk analytics landscape: how organisations measure physical risk, insure against it, price it, operationalise it, and ultimately compete on it.